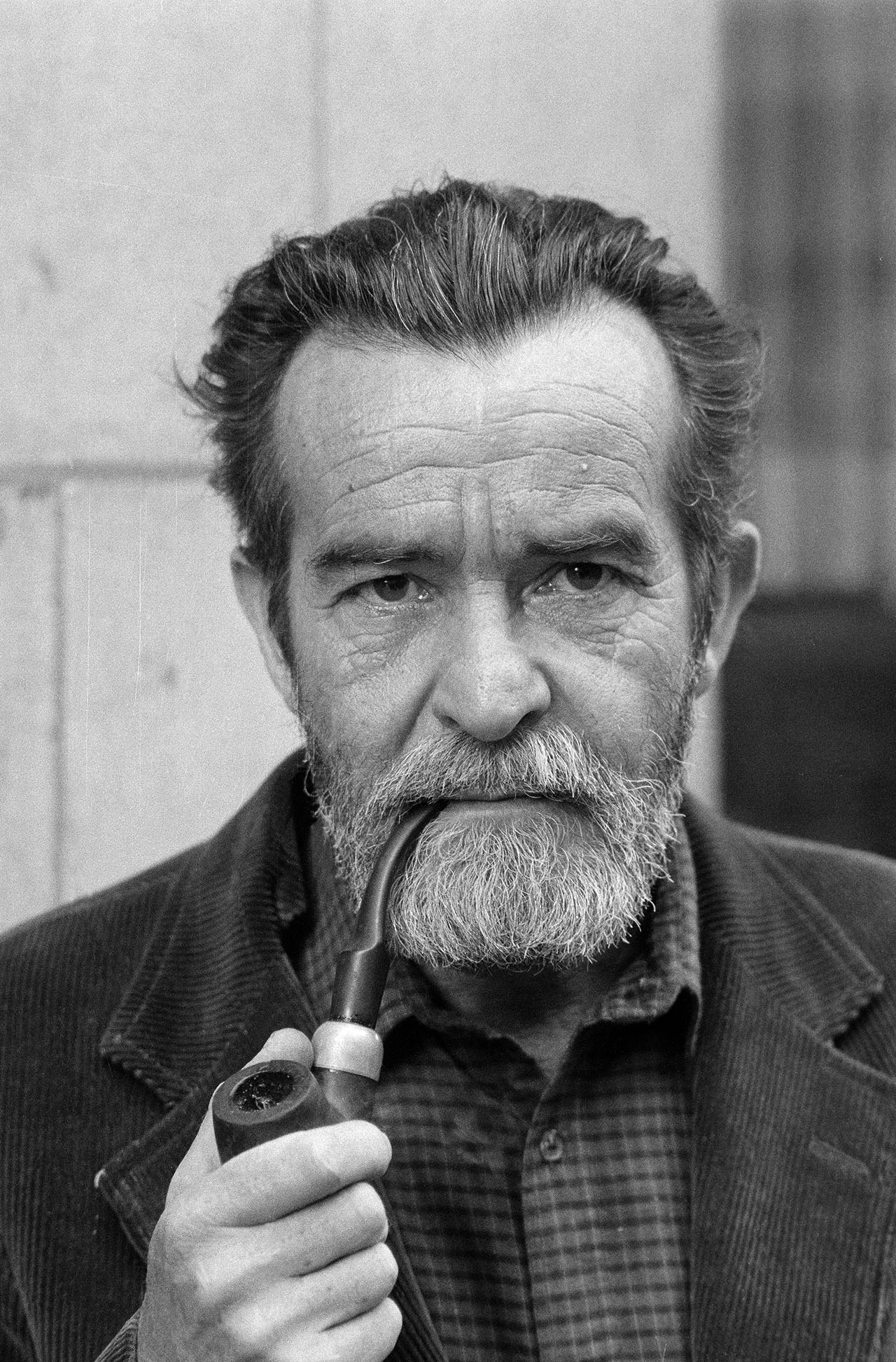

Athol Fugard: Biography

Athol Fugard, in full Athol Harold Lannigan Fugard, (born June 11, 1932, Middelburg, South Africa), South African dramatist, actor, and director who became internationally known for his penetrating and pessimistic analyses of South African society during the apartheid period.

Fugard’s earliest plays were No-Good Friday and Nongogo, but it was The Blood Knot (1963) that established his reputation. The Blood Knot, dealing with brothers who fall on opposite sides of the racial colour line, was the first in a sequence Fugard called “The Family Trilogy.” The series continued with Hello and Goodbye (1965) and Boesman and Lena (1969).

Fugard’s willingness to sacrifice character to symbolism caused some critics to question his commitment. Provoked by such criticism, Fugard began to question the nature of his art and his emulation of European dramatists. He began a more imagist approach to drama, not using any prior script but merely giving actors what he called “a mandate” to work around “a cluster of images.” From this technique derived the imaginative if shapeless drama of Orestes (1978) and the documentary expressiveness of Sizwe Bansi Is Dead, The Island, and Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act (all published in Statements: Three Plays, 1974).

A much more traditionally structured play, Dimetos (1977), was performed at the 1975 Edinburgh Festival. A Lesson from Aloes (published 1981) and “Master Harold”…and the Boys (1982) were performed to much acclaim in London and New York City, as was The Road to Mecca (1985; film 1992).

After the dismantling of apartheid laws in 1990–91, Fugard’s focus turned increasingly to his personal history. In 1994 he published the memoir Cousins, and throughout the 1990s he wrote plays—including Playland (1992), Valley Song (1996), and The Captain’s Tiger (1997)—that have strong autobiographical elements.

Subsequent plays included Sorrows and Rejoicings (2002), about a poet who returns to South Africa after years of exile; Victory (2009), a stark examination of post-apartheid South Africa; The Train Driver (2010), an allegorical meditation on white South Africans’ collective guilt about apartheid; and The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek (2015), which explores South Africa both before and after apartheid.

- Athol Fugard

Fugard: Aesthetic vision of Theatre

In the preface to My Life (1994), Athol Fugard articulates the two basic needs that clearly inform and shape his theatre. The first is his general concern with South African situation and the world around him.

Fugard has expressed his frustration and impatience with “the middle aged and the ageing,” whom he has accused of being merely rhetorical and bombastic about the South African predicament, and articulates the urgent need for an alternative voice to be provided by the young South Africans. He sees in the youth an appropriate and inevitable human and artistic vehicle that can be used to mould the future destiny of their country.

The other need is personal, his personal past and vision of a new South Africa. As a theatre practitioner, it is Fugard’s thinking that the new political dispensation in South Africa requires a new artistic form. He attempts to achieve this by the renewal of his faith in the spoken word.

Fugard’s position is that his entire writing career has been an attempt to bring the above two elements: youths and words, into a form of harmony. But tied to these two basic needs is Fugard’s aesthetic vision of the theatre to bear witness, on behalf of the oppressed black South Africans, to the insufferable human conditions, the psychological struggles of the individuals to overcome these conditions and the role of art and the artists in the critical moment of the South African desperate situations to achieve freedom.